May 2020

“When things don’t go the way we planned in our process, that can be an important, generative moment. I think there’s a space, in all practices, for improvisation, spontaneity and intuition.”

studioELL is thrilled to welcome Nyeema Morgan as our inaugural studioVISIT artist. A virtual visiting artist series, studioVISIT is a new program devoted to providing access into the artist’s studio featuring a discussion focused on practice.

Nyeema Morgan is a Chicago based, interdisciplinary artist. She earned an MFA from California College of the Arts and a BFA from Cooper Union School of Art.

Morgan’s CV is impressive, with exhibitions at The Drawing Center, NY; Art in General, NY; The Bindery Projects, MN; and South Hill Park Arts Center, Bracknell, UK; to name a few. She is the recipient of an Art Matters Grant, NY; and a Joan Mitchell Painters & Sculptors Grant, NY; and has participated in residencies at Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, NY; and the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, ME, among others.

Monoprint, artist’s cherry frame and rubber, 85.5 x 43 x 36 in.

Image courtesy of Grant Wahlquist Gallery, Portland, ME

ARTIST STATEMENT

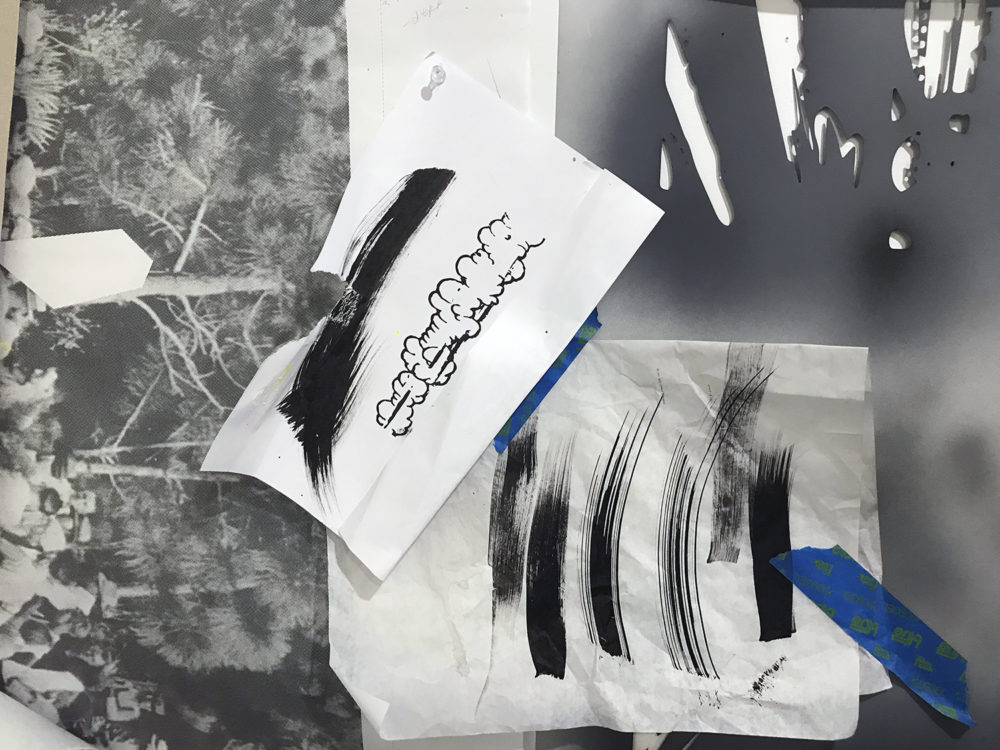

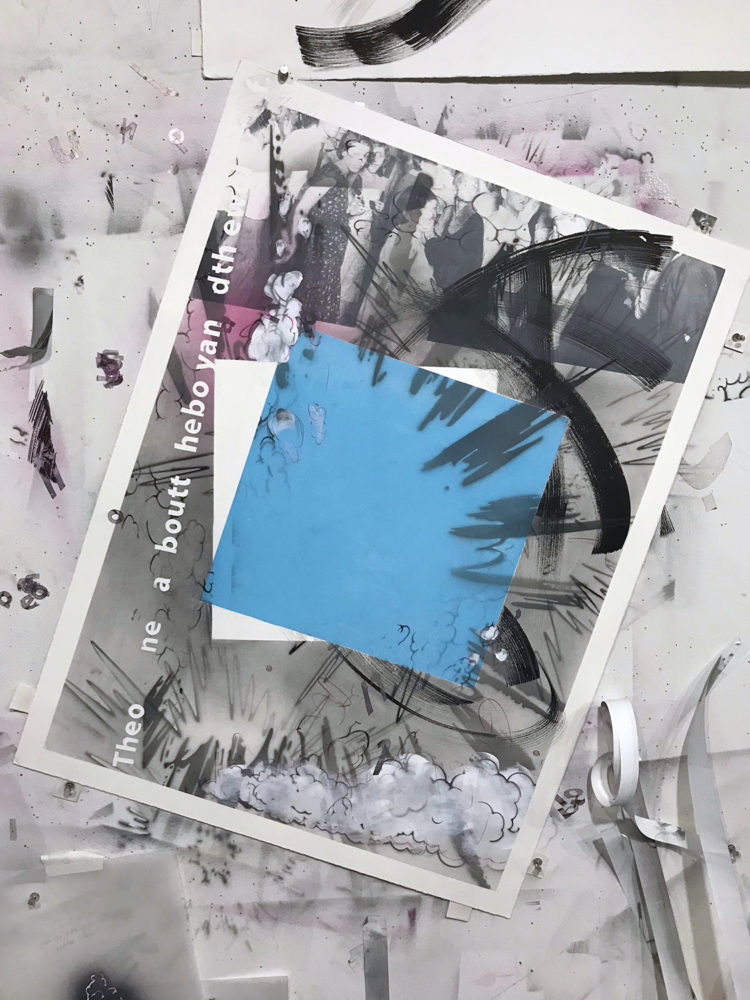

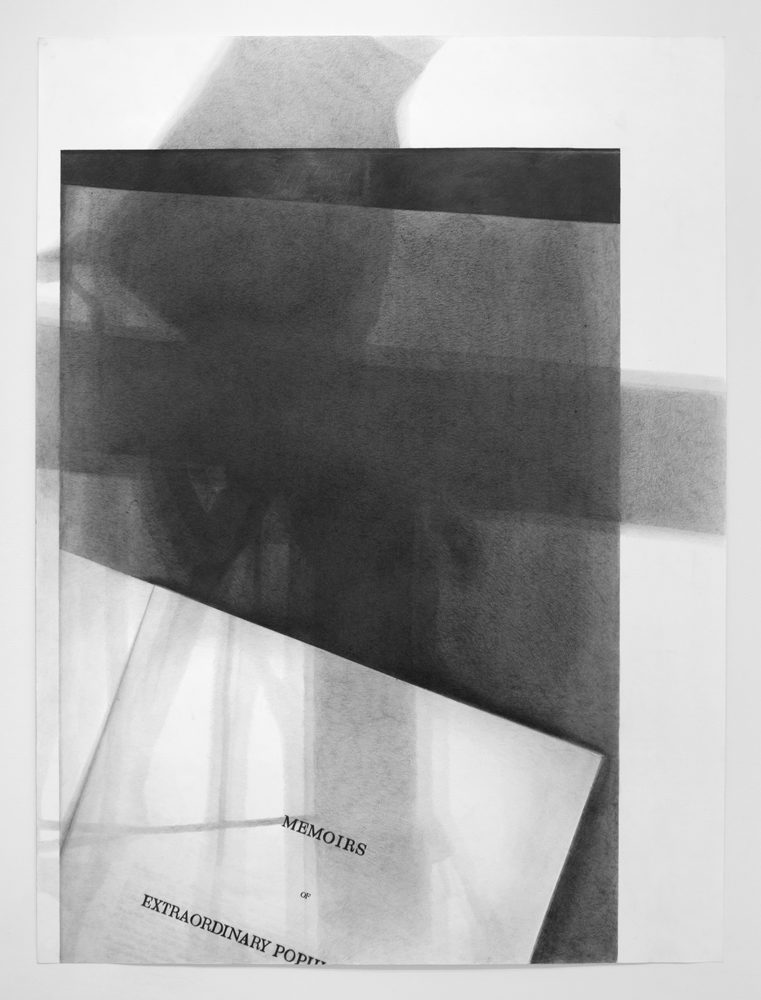

I make art in response to philosophical conflicts in my everyday encounters with images and objects. Referencing familiar artifacts like pictures of Robin Hood, canonical artworks, recipes, book pages and online message board conversations, I’m negotiating personal and cultural economies of information. These types of ubiquitous cultural materials serve as a starting point for me to reflect on how we articulate and construct meaning within a complex system of socio-political relations.

IN DISCUSSION

john ros / There is such a rich sense of collage in your work. A density that at once obscures with redaction and overlay, and reveals with glimpse and fragment. There is a poetic structure and decisive language. You provide us with enough information to leave us silent in contemplation — wandering for more. There is a poetic efficiency in your visual language. Do you think about visual language in this way? How much does poetry play in your research? Are you reading any good poetry at present?

Nyeema Morgan / Thank you for that thoughtful attention. You know, I’ve never used the word ‘collage’ to describe my work — ’layered’ or ‘conflated’ perhaps which, yes, are primary elements of collage. I think of collage in the way I think about painting — as being about surface, which is interesting to me conceptually in the ways you’ve mentioned — overlay and obfuscation. My concern with surface is as something to be transgressed rather than built. So the porosity/fragmentation of my images are very intentional as a way to undermine the politics of surface. I identify primarily as a drawer, so I’m more interested in boundaries, and edges. That’s just an idiosyncratic characteristic of my perception. Edges and contours stand out more prominently than planar surfaces. To me the edge, the line, is that active and efficient articulation of space as opposed to the point which is static. The line is the precipice, a site of radical intervention. And if my work, like you said, “leaves us silent in contemplation”, that is the place where I would hope that happens — on that precipice, a space of uncertain shift where a multitude of questions arise.

While I’m working, I do think about poetic structures or literary devices related to poetry. Not as a means to build my work but I think it has more to do with the relationship between poetics and aesthetics, so naturally I’m thinking about things like movement (rhythm), symbolism and structure within visual language.

jr / The idea of transgressing surface is so important. Throughout the work it reveals itself in the power of image and interrelations between materials and surface — and this is where the poetry exists. The politics of surface in direct relation to the line creates the radical moment you are after. I can’t help but think of boundaries, limitations, fences — but also skin and personal boundary and all the implications that our bodies have within dominant external criteria. The porous quality allows for lots of grey in a world that is so often defined in absolute terms, which also allows for a certain amount of subtlety and/or ambiguity. How does this resolve itself through your process? In prescription or improvisation, how or when do you decide to allow for a softer or heavier hand?

NM / Life is all about ambiguity, nuance and contradiction. It’s quite frustrating isn’t it — to try to rationalize a world so immense and convoluted; to perceive it, let alone organize, articulate and make meaning from it? Process philosopher Alfred North Whitehead described the world as a conglomeration of realized facts that we witness only as select “pulsations of actuality” which carry the full context of the antecedent universe. Our perception of the world is fragmented — biased. There’s the power struggle, between constructed realities. Being a Black woman in America, raised in the south by artist parents who grew up in Philly in the 60’s, incredulity and critical mindedness were at the core of my intellection from a young age. This was, and still is, about survival — acute observation and understanding that a dominant bias prevails and ‘seeing’ through what’s presented. (My late mother would always make a distinction between ‘looking’ and ‘seeing’). So transgressing surface — absolutely.

In regards to my work, and my process, it’s important that how I work and the decisions I make encourage ‘seeing’. How I handle material and form has some sensual appeal but never without eliciting suspicion or doubt — the ambiguity, the grey area. In fact I try not to let the sensual overpower the conceptual. I’m vulnerable to seduction. This is “when”, in my process, I employ a system of stymying a greater conceit to the slickness and surface impenetrability of fabrication.

jr / I love the visual of, “pulsations of actuality.” It feels well connected to creativity and process, as Whitehead argues. Your connection to “survival and acute observation” mirrors this visual, as does your mother’s insistence in the difference between ‘looking’ and ‘seeing’. This constant push-pull of life and of art. The persistent and uncomfortable grey that artists seek.

This is the space where vulnerability steps in. Our vulnerability to our observers, but also our vulnerability to ourselves — like being seduced by image, color, light, whatever. Seduction is like the insistence of a reliable trope that comes into the work. Reliable, but often obvious or redundant. I don’t get that sense in your work. Because of how you’ve described how projects develop, it seems like you are constantly reinventing or at least re-imagining your own sets of criteria. I guess what I am saying is, there is no reliable mark or noticeable quip to point to — no tropic gesture. Your visual language does not seem to rely on them. Is this actually the case? Are there moments, or rituals, or nuanced nods that may be unnoticeable to the viewer that you do rely on?

NM / You know, when I do artist talks I’m always taken aback when someone says “Your works look so different from one project to the next”. I never know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing. This observation used to make me feel uncomfortable. Now I’m okay with it as a characteristic of my practice. I think this is attributed to my concession to “what the work needs” rather than what I want. I don’t trust what I want— at least when it comes to Art or art making— actually with most things. I’m always reconsidering my criteria and allowing the possibility for the work to deviate in some way or another from what I intended. To paraphrase my undergraduate professor at Cooper Union, Irwin Rubin — “Whatever your first idea is, it’s bad. Throw it away. Your second idea, that’s bad too — throw that away. Your third idea? It’s okay. Hang onto that one.” In all of my works there has always been a moment in my process where I’m in conflict with myself — where I question my motives. In my series of large scale drawings, Like It Is (2010-16) it was the revelatory moment when I began rendering incidental shadows into the drawings. When I started making them in 2010 I was hell-bent on relying on certain conventions of image making and representational drawing — centered image, immaculate renderings. They were nice but other than their size, they were staid and boring. But I was self satisfied which I know now to be suspicious of. So if there is any consistent ritual that I fall back on, it would be that moment of conflict or resistance that alters the trajectory of the work a bit. Now, rather than being frustrated by that moment, I get excited because I know I’m about to flip myself the bird and do something exciting.

jr / I love the idea of you flipping the bird to yourself in the studio — I think that’s what it takes to stay on top of ourselves. Of course we want to feel certain successes in the studio too, but as you mention, when we rely on these too heavily, they become tired and obvious. The need for excitement! Staying curious and on top of yourself in terms of self-awareness and poignancy — learning when to listen to yourself and when to push yourself. “Ability to fail” is built into my studio syllabi. Do you have any advice for those struggling with these aspects in their studio? How can young artists become more comfortable with failure?

NM / I’d encourage young artists to consider how they define failure and success. I would suggest adopting a way of measuring success that is internal to their practice — a barometer that can constantly be recalibrated as their work evolves. Maybe we should stop using the word ‘failure’ when it relates to our art making. When things don’t go the way we planned in our process, that can be an important, generative moment. I think there’s a space, in all practices, for improvisation, spontaneity and intuition.

jr / What takes precedence in your practice? The image? the material? or the process? Not that these need to be mutually exclusive — but some pieces like, horror horror (2018) feel reductive in their process, almost as if you start with the resulting image and somehow work back from there. Others, like, Like It Is (2010-2016) or, Forty-Seven Easy Poundcakes Like grandma Use To Make (2007 – 2012), feel procedural, with resulting imagery a remnant of process. Do either of these thoughts enter your practice? Are there parameters for how projects progress?

NM / It depends on the work. I begin with found cultural material as a reference so there is always a form I’m responding to and I begin to interrogate it — its necessity, how it functions in the world and upon whom does it function. Those particular questions direct me to particular processes, materials or subsequent images. And all three aspects of the work are extremely important in varying degrees depending on whether the work is intended to be warmer and more sensual or colder and more procedural. Whatever the work, it is a very delicate set of relationships that I’m tuning. And although their process may seem fairly technical, there is an element of improvisation — unplanned decisions I’ve come to rely on as disruptions. Especially at times when I feel like the process is driving the work too narrowly.

jr / I love the descriptions of warmer, more sensual, and colder, more procedural and how they seem connected to technical and improvised processes — and the sense that process, materials or imagery can lead to narrowness or openness. Not to put it too romantically, but the conflict and/or contradiction seems to be a major force. Contraction can lead to some of the best reactions, especially in a world where bilateral thinking prevails. How do you make sense of this polarity in the practice overall? When is contradiction welcomed? When is it not?

NM / In Art we’re dealing with aesthetics, semiotics, psychology — none of which are based on empirical sciences or are universal, so it’s important to question the foundation that they lie upon and how Art or language function within shifting contexts. For me, contradiction draws attention to assumptions that may go unexamined or uncontested. I appreciate the “unsettledness” of contradiction as a foil to dogmatism. The impetus for my own work is some vague desire for reconciliation between oppositions or antagonisms. Even though the final work may not function in that way, at the very least it presents, and opens, to borrow Trinh T. Minh-ha’s metaphor for translation, a space where elements representing different subjectivities spiral amongst each other without one subsuming the other.

Image courtesy of the artist

jr / I think the greatest role an artist can play is as a member of a community. Whether witnessing, activating, organizing, teaching, communicating — the artist stays aware and active. Your desire of subversion within the politics of surface understands this important role. On a practical note, how do you stay informed? Where do you collect your materials? And what sources/moments most activate your studio space or practice? After spending time with this material, how does the dance between processes, materials or subsequent imagery initiate?

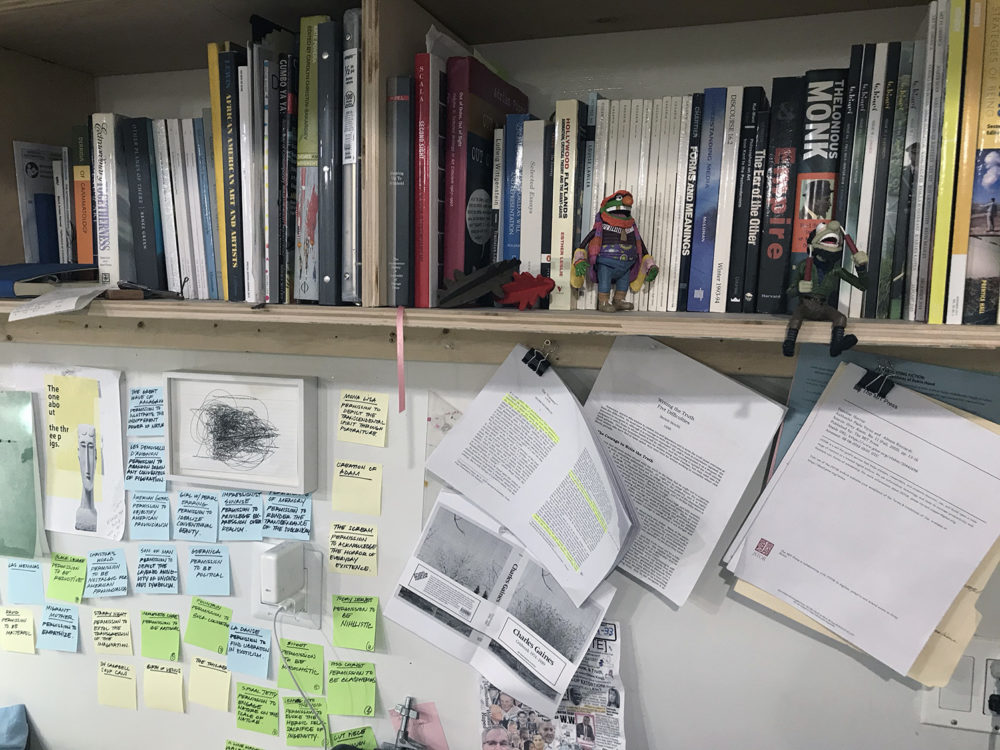

NM / I stay informed by trying to be present — consciously. By being observant and active in the world through teaching and dialoguing with peers. As someone who began teaching rather reluctantly, I’ve grown to love the work, the research and the interaction with students. They’re a different generation so they always challenge what I assume is constant, like our relationship to images and how we perceive the world and ourselves in it. Aside from teaching, I do a lot of research: reading — and shamefully — watching a lot of television. It’s such an honest representation of our base cultural desires. If you were gobsmacked by how 45 was elected, all you had to do was look back at the last 20 years of TV to see the rise of the antisocial, narcissistic hero. These observed cultural phenomena spark questions that fold back into thoughts about my own lived experiences. That’s what really activates my practice. I don’t know if I can really describe the dance between process, materials and imagery. Like I mentioned before, I start by responding to something (an idea, an interaction, an image) that exists in the world, from there questions that arise point me in certain directions. The questions are usually epistemological in nature. The digital drawings, Forty-Seven Easy Poundcakes like grandma Use To Make, were inspired by questions of authenticity and quintessence while thinking about my grandmother’s ‘easy pound cake recipe’ and others of the same name that I had found online. Throughout the process I’m thinking about the structural intricacies of language and communication. Both dialogically, and through the interactions of material and form. It’s difficult to be describing my process because it’s not a single linear progression but is more rhizomatic.

jr / Being continuously present can take its toll. Being present, in some ways, has become a new form of activism — an important aspect to staying informed — and being involved in any space of activism or subversion. But it is also exhausting. Connecting to source material, when TV watching or reading or listening becomes overwhelmingly a space for fodder, and not distraction or escape, can being present send us into overload?

Speaking of distraction — in the age of endless convenience — what happens to our ability to be present? Do you think modes of convenience could move us in a direction of being less present? Or can convenience bring us closer to the present? How have you used modern day conveniences? How have they worked against you?

NM / I absolutely believe convenience, to an extreme, makes us less present, yes. As a teacher, I’ve noticed with each generation of students I teach, the more immersed their generation is in information culture, the less curious they are — the less motivated they are to ask questions or find answers to the questions they do have. Or even worse, they don’t have the ability to formulate thoughtful questions. (This isn’t all of my students but enough to strike concern) I think that has to do with access to information, their proximity to information. Growing up my, access to information was not as convenient. It took some work, some motivation, an effort that was mentally and physically felt. All this to say, I don’t take the modern convenience of easy access for granted. It still amazes me. I do a lot of my research online whether it’s for my art making or administrative work related to my practice. But it’s easy for me to fall down the rabbit hole. So I try to make my engagement with these conveniences more qualitative than quantitative. I don’t feel compelled to know everything about X, Y and Z. It’s important to ask ourselves is this, or that, specific information significant. Is it something I instrumentalize to the effect of actually doing something (small or large), or is it just kind of… anaesthetizing. At the moment, we’re living through this Covid-19 pandemic. I’ve been strictly self-quarantined with my partner and two young kids for a solid month. I watch 15 minutes of the news in the morning (either tv or reading CDC or W.H.O. updates online) and another 15 at the end of the day— that’s it. I don’t spend hours scouring the internet reading articles about the pandemic on this site or that site. It can be too much and redundant.

jr / You’ve hit on curiosity in our students, or rather, in many cases, the lack of curiosity. I think this is one of the greatest threats to the studio arts and in visual culture in years to come. Have you come up with ways to confront this in the courses you teach?

NM / It helps to contextualize their role as students and their educational, and subsequently professional, pursuits in a very specific moment in time. Often when I start working with a group of young students, the mood of the first day is like: “Okay, we’re here. Now what?” Well, where is ‘here’ and what is ‘now’? My role as a teacher is really that of a mediator — between my students (their perception, understanding and articulation) and the world (phenomenological, natural, social, political and that of the inner self). I try to instigate, as well, by uppending their presumptions about whatever it is that is at the forefront of their consciousness. This usually gets them agitated, frustrated or excited into action — it sparks questions that charge their critical positioning. Then subsequently, ideally, their research and making. It’s also important to help them recognize the value of their education, beyond the monetary cost. Whether they are working towards developing an advanced set of skills or knowledge base, their education does not just serve them as a means to acquire a justified living, or wealth and recognition — that whatever it is they end up doing, it has a social function. Contrary to the trope of the solitary, tortured artist, Art is not made in a vacuum— it’s a collective endeavor. They are a part of something bigger than themselves.

“The studio work invigorates me so that I can be a functioning, rational, empathetic, responsible citizen in the social world … I should emphasize when I say ‘responsible citizen’, I am of the firm belief that critical mindedness is a civic responsibility.”

jr / Being present requires so much more energy than being a spectator — seeing not just looking — bearing witness. This provides a space of agency. It is empowering, especially when dealing in opposition to any dominant structure. Do vagaries or abstractions in the studio translate to empowering the citizen in you? Do you see the activities of being in and out of the studio as different? Or are these more of a symbiotic relationship? I ask because I make no distinction between my artist-self and my citizen-self. To me, studio practice is constant. I suppose I am touching on interconnections of the everyday and art and how ideas of practice can intertwine throughout our lives.

NM / To me, being ‘present’ and being a ‘spectator’ are one in the same. They are both passive. ‘Seeing’ is just the beginning and hopefully it incites some type of significant and provoking action. To answer your question about the influence that “vagaries and abstractions” have in my studio, ‘yes’ they do empower me not just within the studio but all aspects of my life. They’re anathema to convention. The studio work invigorates me so that I can be a functioning, rational, empathetic, responsible citizen in the social world (less so in my art practice, at least less rational and semi-functioning). I should emphasize when I say ‘responsible citizen’, I am of the firm belief that critical mindedness is a civic responsibility.

THE SIX…

Six questions asked of all our guests.

What are you currently reading?

Franco Bifo Berardi’s Futurability and Edward Said’s Representation’s of the Intellectual.

What are you currently watching?

Succession.

What was the last meal you made?

Does cereal count as a meal?

Can you share a recipe?

I improvise in the kitchen so I don’t really follow recipes unless I’m making something ambitious.

Whose studio have you visited recently that really excited you?

Recently? Well, bias heavily considered as matter of convenience (I have to walk through his studio to get to mine) but also because I’m genuinely excited by his work, my partner Mike Cloud’s. His sincerity births really unconventional and risky paintings. It’s very inspiring to witness. I was also recently blown away by a virtual studio visit with artist Nate Young and the new sculpture he’s making for his show at the Driehaus Museum in Chicago.

What have you seen recently (either art; performance; film, music; stage; etc.) that had a significant impact on you and your work?

That’s a big one. What hasn’t had an influence on my work? Pope L.’s 2004 Skowhegan Lecture has been resonating with me for some time. Then there’s music, always music. Everything from Can to Philip Bailey to Captain Beefheart which heavily affects my energy in the studio.

A sincere thanks to Nyeema from john ros and studioELL — thank you for the generosity you’ve shown in sharing your studio practice with us.

john ros is a Brooklyn-based, multi-disciplinary artist, professor and curator. They obtained an MFA from Brooklyn College, City University of New York, and a BFA from the State University of New York at Binghamton. john is the founder of studioELL where they currently serve as director and professor. They have over 15 years experience in higher education and 22 years experience curating exhibitions and developing community programming.

This interview was conducted over a series of emails which started with a few initial questions and led to a responsive conversation. The text has been edited slightly for this publication, including a slight shift in the order questions are presented.

studioVISIT Artists

Tash Kahn + john ros | Jeannine Bardo | Dominique Christina | Stephanie Williams | Vishwa Shroff | Chloë Bass | Natalia de Campos + Thiago Szmrecsányi | Elly Clarke | Sameer Kulavoor | Alfonso Fernandez | Nyeema Morgan