IN DISCUSSION

john ros / Your performance-based, collaborative practice takes a very activist role — especially in the realm of workers and citizen rights and fights for democracy, especially focused on Brazil.

I see a lineage of projects, some new, some on-going, some seemingly on hiatus: Syncretic Pleasures, Defend Democracy in Brazil (DDB-NY), ART&COM, Collective Bargain and United Artists & Activists Union — see page 9 for a more complete list.

You are both building an incredibly rich timeline of action and practice in a way that truly blurs lines between activism/protest, art practice and day to day life living in a struggling democracy. Your actions are at once, encouraging, enriching, provoking — but all of this artistic political action must also take its toll — especially when there seems to be attacks at every corner and effecting every aspect of our livelihoods.

There is so much to talk about… lets start with practice. What does your daily artistic practice look like? And… How have the current regimes of Trump and Bolsonaro shaped the daily practice in the last few years?

Natalia de Campos / Daily artistic practice for me is a balance between some of the additional jobs I’ve had, that rely on my background as an artist, with a history degree, a producer and a translator, my volunteerism in social justice, and the honing of different skills at different times. I am interested in current events, on how they affect us personally, but also in our social interactions. So certain events, especially those that affect me most, end up in writings at the end of the day, the next day — or they wake me up during the night. I will revisit these writings when creating an object, or performance — when trying to curate an event with some sort of narrative. I base a lot of what manifests as finished performances or finished artworks in my writings, in interviews, in people’s personal accounts or declarations, in collecting sentences and visuals, and in research. Thus, as you can imagine, the politics of today, and the effects they have in our everyday lives, and in the lives of many communities that I support, play a big role in shaping some subjects in my practice, even more so recently.

These subjects and their manifestations affect not only my artistic practice but also deeply affect my role as a citizen of two countries, Brazil and the U.S. In NYC I am involved in many local art and activist communities, such as the cultural center where Thiago and I share a studio, my local community garden, and artists/friends who have shifted and reunited with me through the new realities we all face. An example is the work through the Defend Democracy in Brazil Committee (DDB), founded by Brazilian friends who met other Brazilians and supporters on our street protests and performances. I am now able to see more connections and similarities between the two countries, and other countries with all the struggles we currently face. Today’s interconnectivity teaches us a lot about manipulation of content and narrative of these realities. As an artist, a communicator, both visually and as a performer, language has always been at the center of my practice. The way I have manifested my concerns has been influenced or altered to reflect our use of media today.

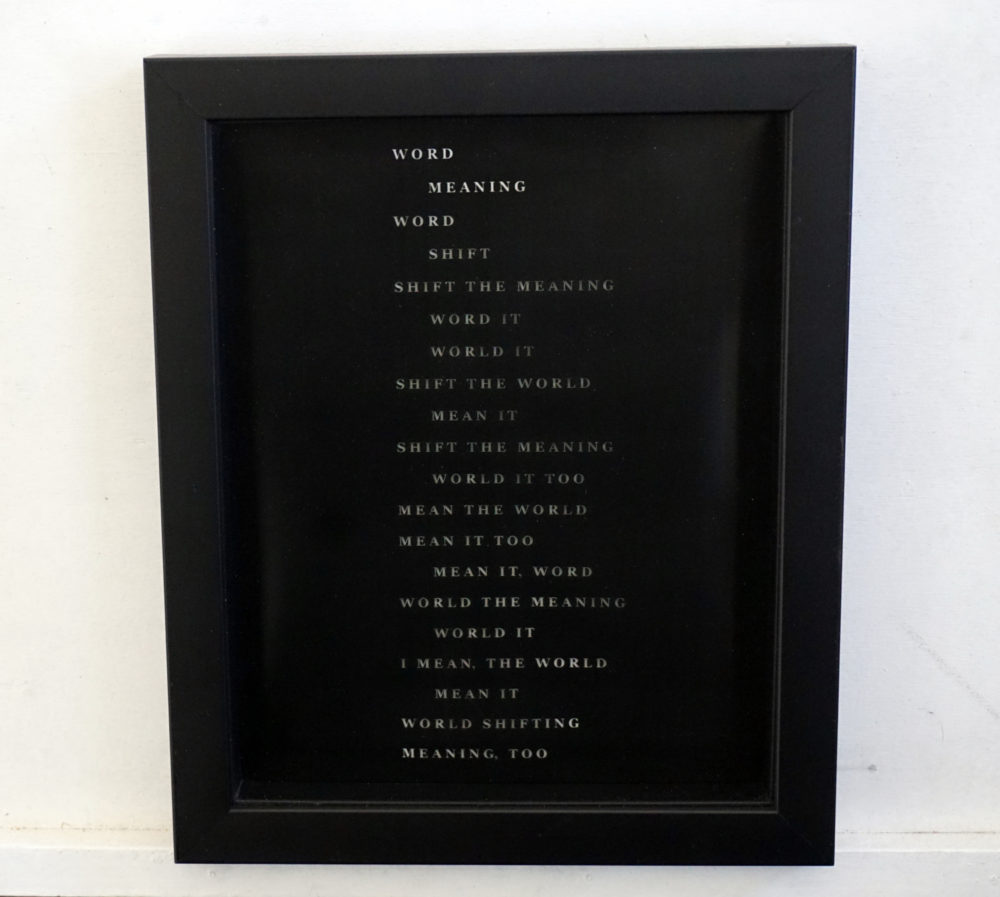

In a visual poem, for instance — as I call my ‘translation’ of a written poem to its visual expression — I worry about the way people relate to the visual message, how they might become interactors. Presently, with everyone being a producer of and interactor with so many messages via social media or other forms of personal manifestation/interaction, I put narrative at the top of my priorities when manifesting something visually, or performatively myself. I still maintain a non-linear or not-literal narrative, but I feel I must now worry more about the multiple interpretations a message might take.

In other times, I would examine a word, expression, or sound for its own qualities — the meaning, the pronunciation, the visual aspect, in their repetitions, the cognitive aspect, and particularly, how they sound. Sometimes the sound would be manifested in my performance, in my accent when performing, in a recording, in a visual element, or in how I imagined it sounding in someone’s head, as they read it aloud or in silence to themselves, as it is the case with visual words.

Nowadays I cannot disconnect from its social meaning too — and sometimes reality becomes my most strict ‘editor’, almost like a ‘censor’ — which is horrible, having grown up in a military dictatorship in Brazil (that ended in 1985), it feels like your country’s past is haunting you. This is a reason why I felt a renewed urge to have a more tangible outcome of my work, such as the DDB, which aims to be a vehicle for social change, while it also serves as a steam valve for that anguish to be redirected. This “self-censorship” can also be a huge step towards maturing the artworks and our goals— it makes you need to be, and enjoy being too, more selective, more careful, more caring, about what you put out there — when many of today’s political leaders seem to be ever more careless about spitting out their thoughts without worrying about the consequences.

In my collaborative practice, this is all reflected. I see many and inspiring opportunities in having more than just my interpretation put out in one or more works. The blurring of lines between my thoughts and those of my collaborators, with Thiago’s even more, during the process and with the results — and those of our audiences/interactors is what really makes the work ‘complete’ in my view — or what makes them getting closer towards some sort of satisfactory completion. Otherwise they are just proposals, maybe?

Artists interacted with the Essex Street Market & vendors.

Cuchifritos Gallery in the Essex Street Market, a project of Artists Alliance, Inc.

Photo credit: Mauro Restiffe

Thiago Szmrecsányi / As immigrants we somehow live in two worlds and often have to balance different realities. With Bolsonaro and Trump things started to look more alike, as if coming from one mastermind. Is this a sign of globalization, of an extreme concentration of power?

I believe that as artists we may suffer the consequences and feel despair with the political landscape in both countries. Yet, this was not why my artistic practice got entangled in political matters. Realizing and comparing the differences, in daily life affairs affecting artists from two important art centers such as São Paulo and New York, is perhaps a more enticing ground. In an immediate way, I am more in touch, attracted and shaped by local matters than by the predominant national or international order.

This is one of the reasons why I choose to work with local second hand recycled materials, creating artworks produced from things that are found on the streets, or rejected by other artists with studios in our same building, in the Lower East Side. I transform discarded utilitarian objects through a series of actions that challenge the functional purpose of the materials, the way in which they operate and how they are made. In doing so, , I suggest alternative ways of being, seeing, or making.

Going way back in spirit and in age, I started to participate in the New York artistic life in the late 80’s and early 90’s East Village and the Lower East Side. Our lifestyle already came under attack by the Giulliani administration, with the zero tolerance policies and high rent increases. Our studio building was put in the auction block by the city. The fight to keep our spaces forced us to forge stronger alliances with the community and to act as a collective.

Natalia became my studio mate in the early 2000’s. Our first collaborations were more defined in scope. I built sets and props for some of her shows. In the Essex Street Market and at Cuchifritos Project Space, where we curated and produced two shows, LOCAL, 2002 and insert, 2003-04, our disciplines started to get more mixed and social practice became more effective.

In recent years a new impulse for me to create socially interactive work came from an open call from the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning to participate in Jamaica Flux 2016. I had already participated as an art handler in other Jamaica Flux and I was fascinated with the commercial vibrancy and the ethnic mixture from the area. Since we already had created two projects in a public market, envisioning ART&COM and proposing it for a brick and mortar mall was not a huge step.

At the same time, we were also experiencing the deconstruction of the Brazilian democracy through lawfare, fake news, and an impeachment without a real cause. Brazilians abroad started to gather and mobilize against the ongoing coup. We and a group of friends formed the Defend Democracy in Brazil Committee. Art was used to create signs and performances that used New York as a stage to attract the attention of the media. Our studio was a part of producing a lot of it. We also got connected to many other Brazilian filmmakers, video producers, photographers and artists who were willing to denounce what was happening.

We engaged multiple forms of street protest and formed alliances with other local groups that were protesting for similar reasons. We then also applied this knowledge and practice to the art context such as in Collective Bargain, our participation in Art in Odd Places in 2017, or even in the relocation of ART&COM to an art fair environment in São Paulo, Brazil.