jr / Yes, I definitely mean payback in the terms you have defined — how we define success for ourselves or for a particular project. Your process and interaction in and out of projects seems fluid — almost like a rhythmic dance. It appears nothing ever really has an expiration date and something might always become something else.

I really love the idea of the line between the real and the fictional or artistic. I imagine process and/or play is mostly intuitive and improvisational — but not without meticulously planned elements and/or a sense of urgency depending on the project. How have you most successfully involved non-artists? Do you find a certain level of education or explanation needs to come into play when your audience broadens to include these participants?

NdC / Bringing projects to the streets, or parks and malls, have had a very interesting effect with non-artists involved. Because there are always non-artists who come to performances at universities or galleries where we have shown, where the setting is more formal, and perhaps more intimidating, so it seems that’s where the expectations are also higher and more rigorous. When you are on the sidewalk or in a park, the participation and reactions are very surprising and enriching, many times in ways we could not have imagined. As an artist-interactor-performer, you have to react or absorb, or even process that interaction, right in the moment, which requires a lot of energy and a different kind of attention. Environments that are so rich and varied like the Essex Street Market, 14th Street, Kings Manor Museum Park in Queens, and Jamaica Colosseum Mall, I think were all very successful projects involving non-artists, though all in different ways.

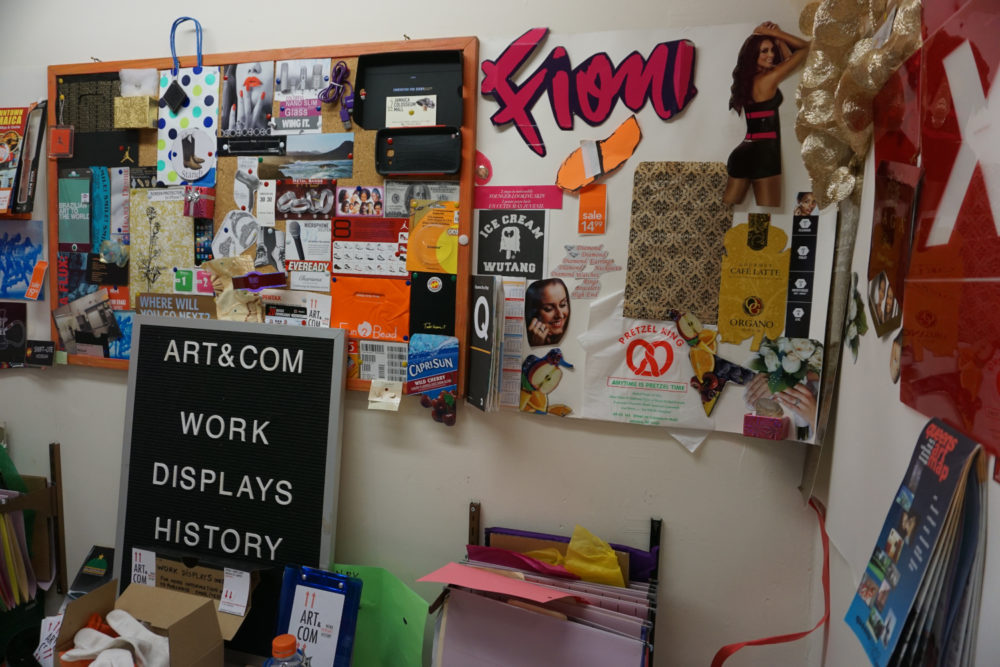

When we brought the first iteration of ART&COM to a gallery in the Lower East Side, after creating it in and for the Jamaica Colosseum Mall, and we called it Re-Location, we felt that we had to give more explanations to an audience that already came prepared to see art. It was a real sweat to encapsulate all the richness and spontaneity it had represented in the mall; that is, it was very hard to explain the mall context outside of the mall. We concluded (afterwards) that maybe we did not need that much explanation at all.

When we brought ART&COM back to the general public, to the streets, with other collaborators, and under the Collective Bargain banner, the reaction was again immediate and spontaneous. I really love that! Collective Bargain on 14th street got the attention of shoppers, union organizers, artists, activists, and more. We were asking people to give their impressions and fill out a form with their profession and demands. We gave them UAAU membership cards, and did not ask for anything else in return. The displays we had in the main posters were “What do We Want?”, “Free Lunch”, “Collective Bargain”. These were read differently by each one of the viewers-participants, as a question and answers, call and responses, demand and explanations. They were words on posters, but the interpretation was so different depending if you saw “Free Lunch” first, or “What do we Want?” first, and so on. Some took them as demands; others took them as offers. Plus, all the rights hanging in a clothes-line provoked direct reaction (internal thoughtful action, in my opinion). That was one of the goals, so I consider that it was super successful.

In the park, the second embodiment of this project, titled Free Time in the Collective Bargain with Tracy Collins again as a collaborator, was immediately embraced, interacted with, and responded to by people from all age groups and backgrounds. We got proposals to organize our United Artists & Activists Union by a labor organizer who passed by, and we also got immediate response from the kids of the neighborhood, who asked “When does Free Time begin?”!! We said — “it started already”, they went crazy! They jumped, played, and interacted with every little thing we brought to the park, so it was total joy.

These are mostly subjective approaches to themes and people outside specific art environments. Then there are the more objective approaches outside too, which happened through the Defend Democracy in Brazil Committee, for instance. When I co-directed the performance with Marcelo Krasilcic, in Manhattan’s “Brazilian Day”, and right after the illegitimate coup on President Dilma Rousseff of Brazil, the message was straightforward, no explanations needed – and in a time of such polarization with Brazilians, let’s just say that the response was straightforward too…

Performance prepared and directed by Natalia de Campos and Marcelo Krasilcic, with members of DDB-NY.

Filmed and edited by Fernanda Faya.

direct link

TS / When preparing to work in areas like a market or a mall, where the predominant activity is not art, we spend time and efforts to introduce ourselves, to explain the objectives of our project, and to invite people to participate in it. Similarly in certain street projects, our first step is to try to map and to understand the area, so that we can better plan our actions, request and find local support. Getting familiar with an area often requires mutual recognition.

Art does not have a fixed meaning that is true for all. In order to become effective, it needs to provide some hints or hooks that unleash reactions on viewers. A label or an explanation may offer a different perspective or another layer of understanding to a project, but they are always secondhand information, not game changers. I also believe that when we are in a public sphere, disputing the attention of a viewer/participant with many other attractions, we must exaggerate things a bit. To me, it is like creating scenic props.

Success in social practice is for me linked to long term effects, the hints and hooks somehow have to resonate with the audience, a different perspective needs to take roots. Perhaps because we were also neighbors and customers of the places where we presented the work, we were able to verify that happening at the Essex Street Market.

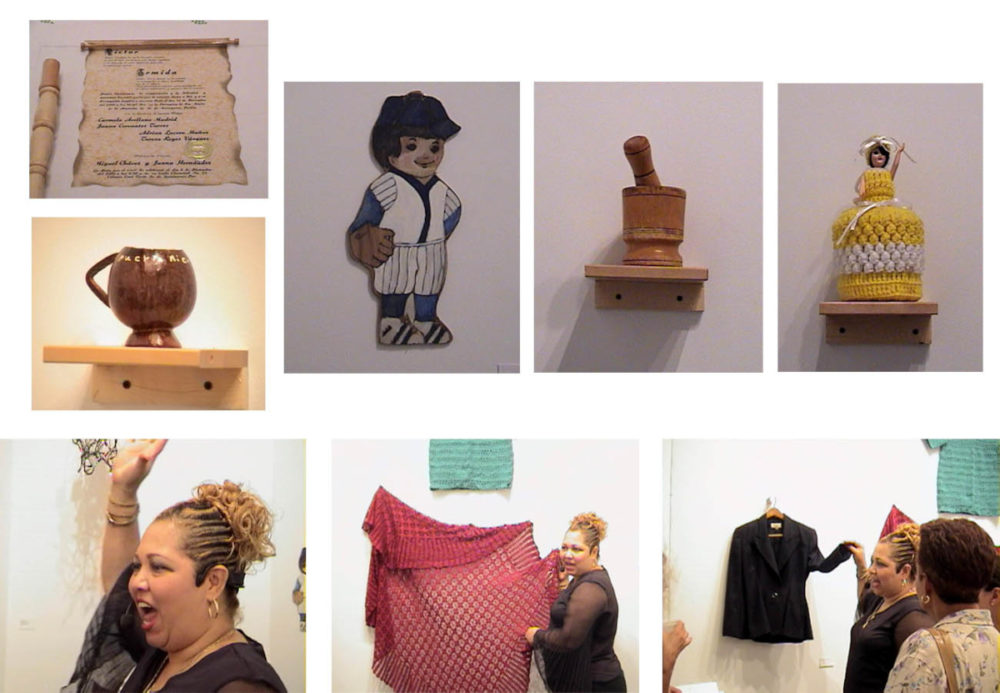

In the Essex Market, we curated and produced LOCAL, 2002, a show where market workers were asked to contribute their ideas around art with an artwork to be shown at the Cuchifritos gallery. Later, I curated and Natalia produced insert, where a group of artists was given a small grant to shop at the market and to produce art with what they acquired. When we returned as customers, we noticed that the butcher, the baker and the barber, all started to present art in their spaces.

In the totally different environment of transnational politics, I think that several artistic strategies that we adopted as members of the Defend Democracy in Brazil Committee have been useful tools in both denouncing the authoritarian nature of the newly established regime, and in gathering and giving voice to segments of society, which have been excluded from the decision making process. These strategies provoke responses from pedestrians, press, and the targets of our demonstrations. Unfortunately, to effect bigger change from abroad, only art is not sufficient.